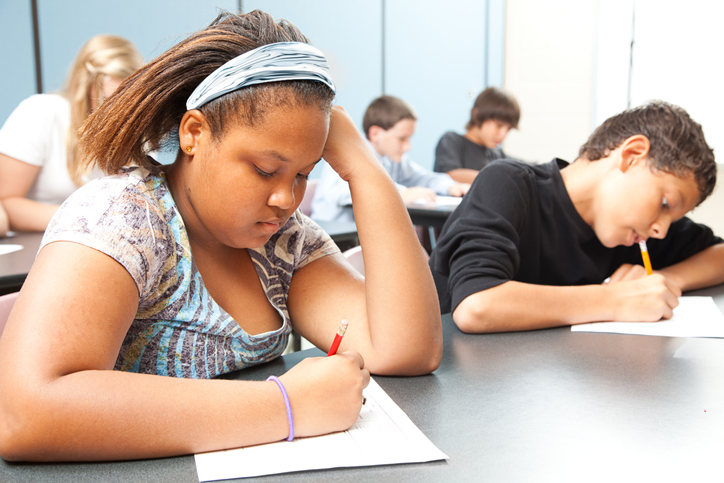

Today’s question is: Is it equitable to have the same grading policy for all students, including multilingual learners? Scroll down to choose a scenario!

A recent Mind/Shift podcast argues that grading is a function of a flawed and obsolete factory-based educational system. Today’s grading is an artifact of that time as “the ways we grade disproportionately favor students with privilege and harm students with less privilege—students of color, from low-income families, who receive special education services, and English learners” (Feldman, 2019, p. xxii).

Think about it. To counteract the grading injustices that prevail, it is suggested that we hold our multilingual learners to the same high expectations and have them be accountable for the identical grade-level content as their peers. If we pursue that line of logic, aren’t we in essence equating equity with equality? \

Grades should reveal what students can do, not serve a punitive purpose.

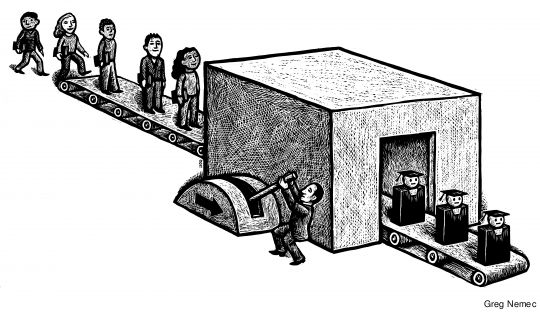

While it’s still a relatively new school year, let’s reassess the role of grading in teaching and learning. Should we retain the status quo for grading students, in particular multilingual learners, when life has changed so drastically since March 2020? Are our students to be punished for factors such as having faulty internet connections or the responsibility for the well-being of siblings?

‘Worthiness’ must be assets-driven as well as linguistically and culturally sensitive.

Assuming that grading is a mainstay of school life (a controversial premise in and of itself), let’s explore three (of many) grading principles that impact multilingual learners:

1) Grades should be meaningful, representing multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate learning based on descriptive, concrete, and actionable feedback.

Grading serves as an evaluative marker of assessment. Whether criterion-referenced and anchored in standards or predicated on an accepted classroom or school policy, grading must be transparent for students. For example, multilingual learners might assign themselves a grade based on data from a series of drafts in one or more languages, preset criteria for success, along with rolling feedback from peers and teachers.

2) Grades should be negotiated between students and teachers according to agreed upon learning goals and evidence of learning in one or more languages.

Student-led conferences are an ideal venue for gaining insight into students’ lived experiences, histories, and social-emotional development. Together multilingual learners and their teachers can review students’ learning targets- what they are learning, how they best learn, and in which languages. Students participating in dual language immersion or developmental bilingual programs with the goal of biliteracy should discuss grades in accordance with the languages of instruction.

3) Grades, as assessment, should reflect learning over time rather than be an end in and of itself.

Being an evaluation tool, grades place a ‘value’ on the extent of progress students have made toward meeting grade-level expectations. Grades should reveal what students can do, not serve a punitive purpose. For multilingual learners this ‘worthiness’ must be assets-driven as well as linguistically and culturally sensitive. Multilingual learners’ accomplishments should represent learning through multiple modalities (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic ways) that leverage their languages and cultural insights.